ROME, Ga. — Joey Watkins was 20 years old when he was sentenced to life in prison for a murder he did not commit. More than two decades later, the 42-year-old walked out a free man.

It's been five months since Floyd County Superior Court Judge Bryan Johnson approved a motion from the district attorney to dismiss the case. The motion stemmed from the work of the Georgia Innocence Project, which introduced new evidence uncovered since the trial - clearing Watkins. That evidence included cell phone records that placed him miles from the scene at the time of the victim's death.

Watkins had been out on bond since January 2023 and ordered to wear an ankle monitor, prior to his exoneration in September.

In the months since his name was officially cleared the cameras have packed up, the national headlines dwindled to an occasional reference, and Watkins went back to his hometown of Rome, Georgia, to try to move on.

Rome wasn't built in a day

"The air conditioning doesn't work," Watkins apologized as he cracked open the front door to a small 800-square-foot property in Rome. "I still have to fix that."

The sound of cars whooshing past on the busy stretch of Martha Berry Highway is silenced as Joey clicks the old door shut and gestures around.

"This is where my business will hopefully take off from," he says, standing in the middle of the nearly empty room. In the corner, a donated old wood desk covered in papers and an unlit "open" sign sits.

"It's a little suck in the 70s style," Watkins laughed as he gestured to the wood-paneled covered walls. "But beggars can't be choosers, I guess."

Watkins clearly takes pride in the building, which he secured in January - exactly a year after he was released on bond. He points out where he and a friend ripped up the old flooring and replaced it with new laminate. He shrugs at the end of the hall when it tapers off into old, crumbling mosaic tile.

"I ran out of money, so I couldn't finish it," he admitted.

Aside from the unfinished floor, the office is missing something else glaringly obvious: business.

Tough getting back to business

After his release, Watkins spent every penny of the money donated to him via an online fundraiser on office space, insurance and licensing needed to open a used car business.

"I made some calls to the bank, and I was like, 'Can I get a line of credit?'" he recalled. Since I've been home, my credit's been good, but I don't have a long credit history. And they're like, 'Yeah, no problem.' So I spent all my money to get prepared."

But after everything was put in place, Watkins was met with a roadblock that might mean his business would end before it even started.

"The banks can't loan me any money or give me a line of credit because I can't show two years of tax returns," Watkins said. "They say it's something they can't get around. So I'm kind out in the water, hoping and praying.”

The shock was personal for Watkins, who hoped to open his used car shop, Watkins Auto Center, after his father's business of the same name went bankrupt under the legal fees needed to clear his name.

"They spent every bit of money they ever made in their life on getting me home," Watkins said, fighting tears. "When I came home, they had absolutely nothing. It's been nothing but a struggle since then.”

(The story continues after the gallery below)

Joey Watkins exonerated in Georgia | Photos

Waiting on a bill

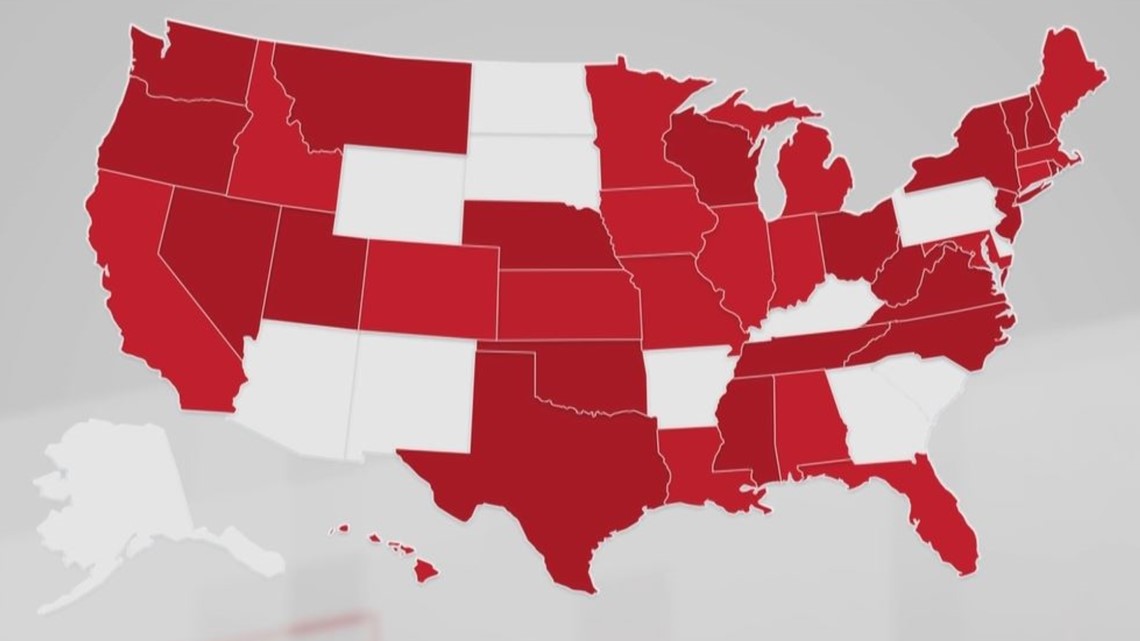

Thirty-eight states and Washington, D.C., have laws in place to compensate wrongfully convicted citizens.

Georgia isn’t one of them.

"When men do time, and they're released, [the state] offers programs for them to enroll in grants, stuff like that," Watkins explained. "But when you're exonerated, you're no longer a convicted felon so you're not eligible for those benefits. It's kind of like, 'Hey, we'll see you. Good luck.'"

A bipartisan bill, HB 364, known as the Wrongful Conviction Compensation Act, was proposed in the House this session to establish an independent board to compensate exonerees. As it stands now, a legislator has to sponsor individual compensation resolutions for each wrongfully convicted person.

Georgia Rep. Katie Dempsey of Rome is sponsoring Watkins' resolution, which would compensate him just over $1.6 million, or $72,000 for each year of wrongful imprisonment.

“This is not what any of us felt we were elected to do, to sit there and hold someone's life in our hands and try to decide what the value on that might be," Dempsey said. "And it's not much when you think of the value of your life."

Watkins watched in the wings as his resolution passed the House in the final hours of Crossover Day to a standing ovation.

"It was emotional," Dempsey said through tears. "Very powerful. Any one of us at any time, from mistaken identity to other things, hold the possibility of something like this happening."

Five other representative-sponsored compensation bills for exonerees also passed the House. The six compensation resolutions would pay out just over $9 million combined. The wrongful imprisonment time served among the exonerees, which include Devonia Inman, Terry Talley, and Darrell Lee Clark, is a combined 129 years.

(The story continues after the gallery below)

Georgia men released from prison after wrongful convictions | PHOTOS

However, with days left in the legislative session, the Wrongful Conviction Compensation Act and all six resolutions sat stalled in the Senate.

"There is resistance just on the principle I think of the state being financially responsible for something that was carried out by county and local officials," Dempsey explained.

"Is it realistic to ask towns like Rome to pay upwards of $2 million?" 11Alive Investigator Savannah Levins asked Dempsey.

"Exactly, our counties would not be able to assume that," Dempsey said. "I think financially, it's coming from the right place. They have certainly been in the state prison system."

As the legislative clock runs out, so do the few dollars Watkins has left to his family name.

“I'm out of money, so I'm on a day-to-day basis now," Watkins said. "If it if it keeps going like this, I'm possibly out of this place."

'I'll swim until I sink'

Watkins says if his compensation resolution passes, he plans to use the money to officially launch his business and pay off his parents' debt. He also said he plans to be an advocate for other wrongfully convicted people in Georgia.

When asked what he wanted to get for himself, he shrugged.

"I'd like a truck, maybe," he said.

But more than money or success, Watkins said he yearns for things like love and time with his remaining living family.

"When I came home the biggest shock was the reality that half your family is gone," he said. "I see all of my friends from back when I was in high school, they're all married with kids that are grown, and you know, I wonder what that feels like."

Watkins said even if he isn't compensated, he'll continue to push through and chase his dreams.

"It's sink or swim, so I'll swim until I sink," Watkins said. "All I can do is thank God. It's all up to Him, and He's got a plan."

Georgia Innocence Project (GIP) has helped free and exonerate 14 people who collectively spent hundreds of years behind bars for crimes they didn’t commit. GIP attorneys are helping advocate for Watkins' compensation resolution, and many others. Learn more about their efforts or donate to GIP's mission here.

You can donate to Watkins' online fundraiser here.