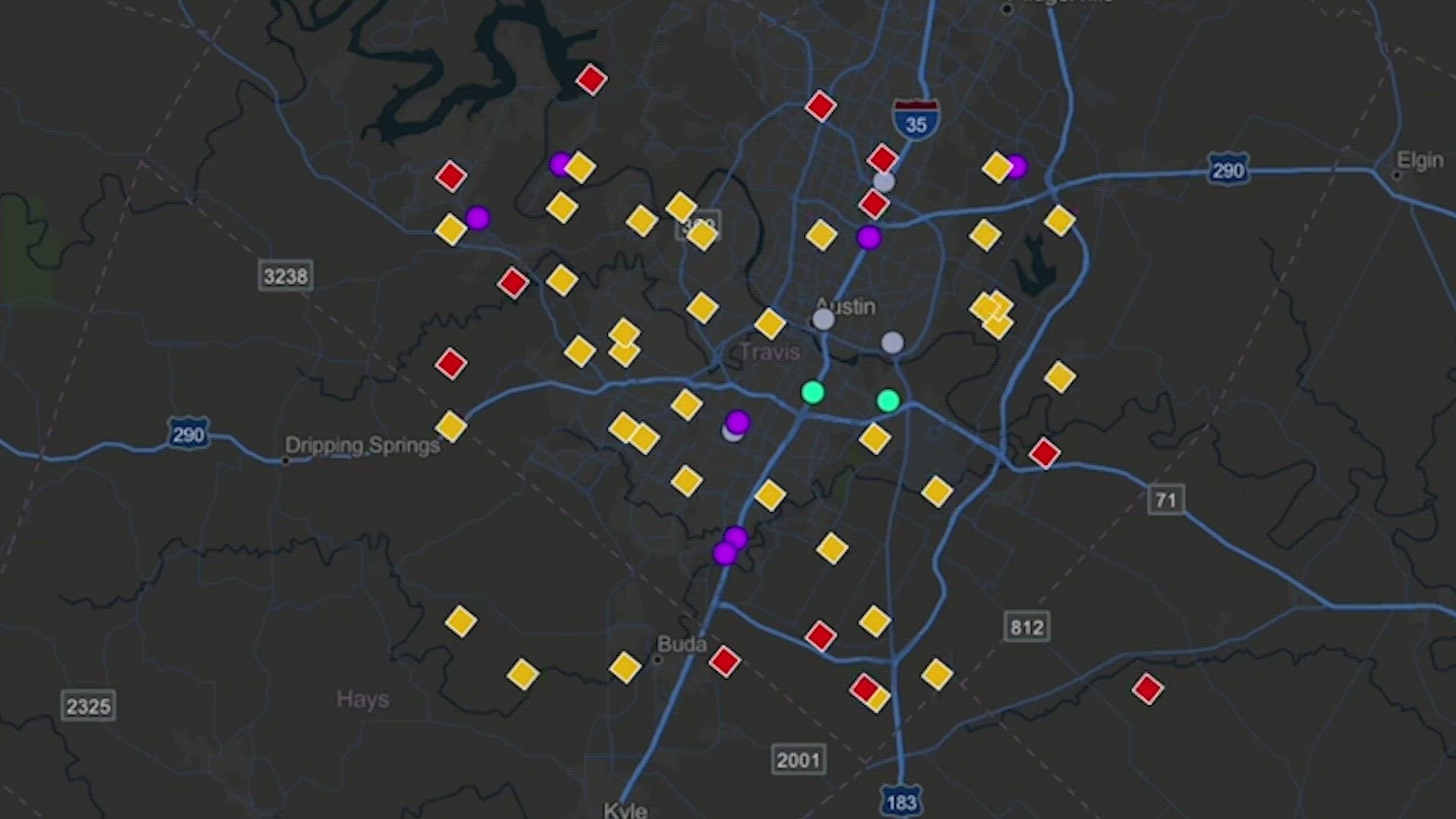

DALLAS — They look like dots on a map.

But they mean so much more.

“Every one of those dots is only moments away from being a fatality,” said Lake Travis Fire Chief Robert Abbott. “We can see the data in real time and share that with our neighbors in the public safety realm.”

Here on the shores of Lake Travis, those dots are pivotal to his community’s fight against the fentanyl epidemic. It’s called the Overdose Mapping and Application Program, or ODMAP.

Abbott says the system’s identified two areas with higher numbers of opioid overdoses. With that information, they’ve been able to put boxes of Narcan – the nasal spray that immediately reverses an opioid overdose – in the right places.

“The reality is we've had more problems in those areas than we thought,” Abbott said.

So how does overdose mapping work?

Agencies enter their overdoses into the ODMAP system, noting where overdose occurred, whether it was fatal, and whether Narcan was given.

“It is a model of response,” said Jeff Beeson, deputy director for the Washington/Baltimore High Intensity Drug Trafficking Area. “If you know what's going on in real time, you have the ability to respond.”

When overdoses spike, the system triggers alerts, which allows emergency medical services to call in extra staff to reduce response times. Hospitals can get prepared for the influx. Treatment professionals can respond to offer help to overdose victims. And for law enforcement, knowing where overdoses occur can lead them to the source of the drugs.

Beeson helped create the system in 2017 as Washington and Baltimore saw a rapid rise in opioid overdoses and officials knew there that something different needed to be done.

“Having that knowledge and that understanding in real time of what's going on in my community, or even a neighboring community, that's going to improve my response protocol and get me in a better position to save lives,” he said.

What about locally?

Many departments in the Austin and Houston area have signed on. So has Plano.

“It's an epidemic at this point and we are very concerned,” said Jennifer Chapman, a police spokesperson in Plano, where fentanyl-related deaths jumped from 12 in 2021 to 24 in 2022.

But most cities in North Texas currently aren’t mapping overdoses.

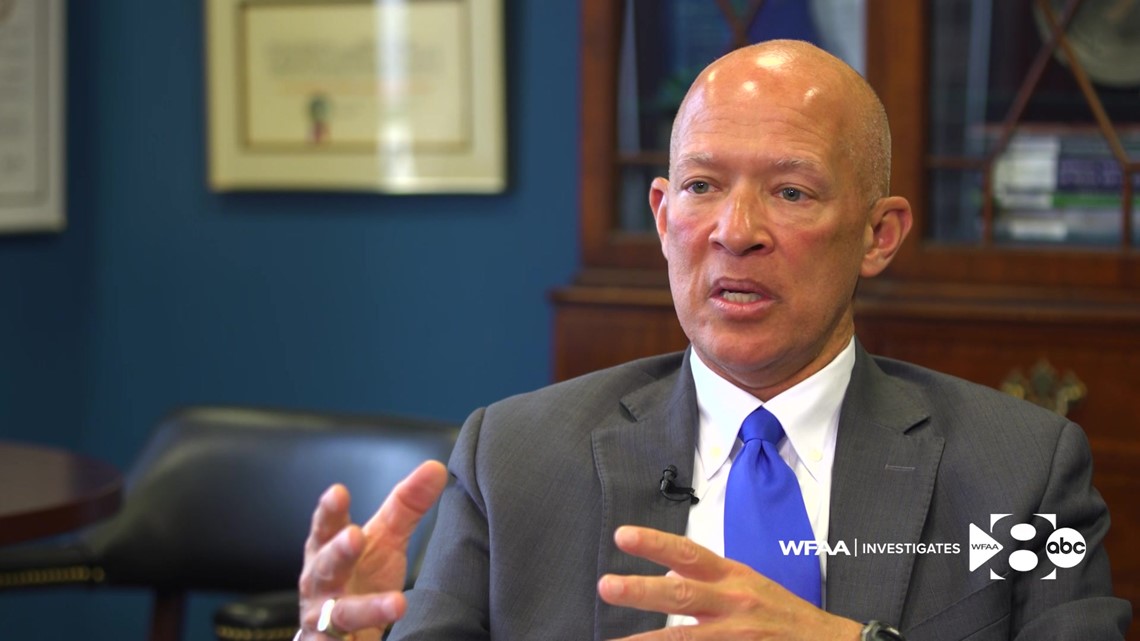

“In order to track it, to understand where it is where it's going, we need that system and we need it fully across all of our municipalities in Dallas County,” said Dallas County District Attorney John Creuzot.

In practice, what that means is that “we don’t get a lot of real-time data,” said Becky Tinney of the Recovery Resource Council, which covers 20 counties in North Texas.

“Oftentimes, the data that we're getting is sometimes a year or more old,” Tinney said.

Dallas

So why hasn’t Dallas been doing it?

For years, as fentanyl deaths skyrocketed, the city wouldn’t let Dallas Fire-Rescue submit overdose information to the database for fear of violating medical privacy laws.

“We had a logjam at the city attorney's office, and they were advising the city council to not go forward with it,” Creuzot said.

Creuzot blames former City Attorney Chris Caso, who retired earlier this year, for the delay in finding a solution. He says he repeatedly asked Caso to explain his concerns about participating in the overdose mapping system.

Through an open records request, he provided WFAA records of his attempts to meet with Caso.

He says only late last year after council members formed a task force did he learn that Caso’s concerns involved medical privacy laws.

“I don't know of any community that has taken that position about this,” Creuzot said. “Communities have looked at as a cost-benefit analysis, and the likelihood of being sued on that is so low. And the benefits are so high that people have moved on.”

Caso, now in private practice, did not respond to requests for comment.

City officials told WFAA that they’ve recently crafted a workaround.

There’s an exemption under current law that allows the information to be shared with a local health authority, officials said.

They’re now sending the overdose information to the county health department, which is shielded from legal claims. The county began sending daily uploads to ODMAP this week, so Dallas’ overdose information is now part of the system and being mapped.

Creuzot’s office also drafted legislation that’s now been sent to the governor to sign into law that shields emergency medical services providers from legal lability.

“This is a huge step forward in getting data into the right hands so that we can direct the resources where they are needed most,” city council member Paula Blackmon told a legislative committee in March.

Tarrant County

What about in Tarrant County? They’re served by MedStar, which covers 400 square miles.

MedStar signed up for the ODMAP program, but hasn’t been able to participate so far.

Lance Sumpter, director of the Texoma HIDTA, says MedStar was willing to provide the data to the overdose database, but their information is maintained by a private entity.

MedStar told WFAA that ImageTrend, the company that maintains MedStar’s patient care reporting system, wanted $15,000 for the initial connection, plus $5,000 annually.

“We couldn't settle on a price that was reasonable that the organization could afford or that I really think we should have to afford,” Sumpter said.

After WFAA started investigating overdose mapping, Medstar and ImageTrend this week reached an agreement. MedStar’s data will soon start flowing into the overdose mapping system.

A MedStar spokesman declined to discuss the specifics, but he credited WFAA with helping the two sides reach an agreement.

An official with ImageTrend told WFAA that the last thing the company would ever want to do is be “seen is as an obstacle to data sharing.”

“When we're having young people and old people dying from overdoses or experiencing overdoses, we can't wait a year to find out how bad the overdose circumstance was,” Sumpter said. “We need to know as soon as possible. So the people that wake up every day professionally to do something about it can respond.

Because those dots could be the difference between life and death.